A CHECKERED PAST

What tapes recorded in a taxi four decades ago reveal about today's New York City

In the thick of the COVID crisis, New York City seemed to morph into a dystopian Gotham, stores shuttered, streets barren, subways overrun by mentally ill, homeless passengers. In the moment, it was difficult to imagine we would recover, but we have come a long way in just a few years.

Still, to this day, an air of dysfunction has lingered, feeding widespread fear about crime, drugs, and urban decay. The New York Post has exploited and exacerbated public fear with a steady stream of tabloid headlines emphasizing the worsening situation: Rape “surges 11%;” Murder “20% above pre-pandemic levels;” Drugs “junkies lying at tourists’ feet.”

A recent headline about crime in Central Park blared: ‘Never felt this unsafe.’ The Post puts much of the blame on migrants, whom it routinely portrays as “destroying” and “terrorizing” the city. In December 2024, when a drunk migrant set a homeless woman, sleeping in a subway car in Brooklyn, on fire and killed her, it only reinforced that narrative.

Admittedly, I walk the streets and ride the subway with a certain apprehension, but, by and large, the tabloid portrait is very much at odds with my perception of New York, developed over nearly four decades as both a resident and a journalist. From my perch, the city has vastly improved on nearly every front.

Until my retirement from the news business in 2023, I reported on the underbelly of the city, and many other places across the globe, for ABC News, CBS 60 Minutes and NBC News, often ensconced in a realm dominated by the corrosive forces of organized crime, terrorism, human rights abuses, and public corruption.

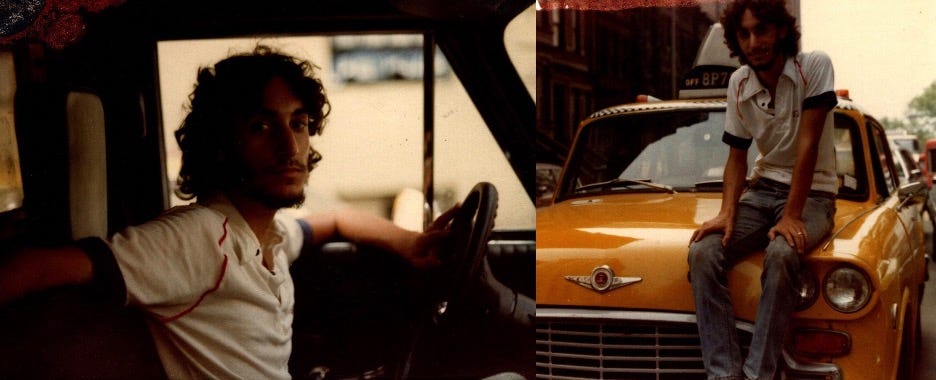

As much as that professional background has informed my perspective, another much earlier experience has had a more profound influence. During three summers in college – 1980, 1981 and 1982 – I drove a New York City taxi. For ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week, I scoured the streets for passengers, in my classic yellow Checker cab, meeting people from all walks of life and visiting nearly every neighborhood throughout the city.

As I remember that era, the streets were filthier and overwhelmed by dysfunction. Subways were overcrowded, covered in graffiti, and unair-conditioned. Buses ran on erratic schedules, spewing hazardous diesel fumes. Rows of burnt-out buildings blighted some neighborhoods, criminals ready to pounce, too dangerous even to stop your car.

But maybe I am misremembering. After all, the mind can distort memories over time. More than once, I have looked back at old journal entries and discovered that my current recollection of an event is contradicted by what actually happened.

As it turns out, I possess the equivalent of old journals from my taxi-driving days: nine hours of audiocassettes I recorded in my cab in the summers of 1981 and 1982 and an envelope marked “Taxi Stuff” containing contemporaneous notes and documents, along with a small collection of grainy photos I took.

I had stashed them in a storage box that sat undisturbed for years on a top shelf in a walk-in closet. A few months ago, I decided to pull down that box and listen to the tapes for the first time since I recorded them.

It was jarring to hear my voice and observations from so long ago, a time capsule, documenting my interactions with passengers from all walks of life, including Wall Street executives, celebrities (among them baseball legend Joe DiMaggio), construction workers, nurses, and elderly recluses, as well as pimps, prostitutes, drug dealers, and their customers.

As emerges from the vignettes below, the tapes, supplemented by my contemporaneous notes, corroborate my recollection of a gritty, decaying, crime-ridden city – but one still imbued with vital urban energy and good-hearted people.

At the same time, the tapes accentuate just how formative an experience driving a cab was for me, in many ways as or more formative than my time in college and graduate school.

In the pre-cellphone, pre-internet era, drivers and passengers either sat in awkward silence or we conversed. I learned how to talk to anyone and everyone, a skill that proved particularly useful in reporting.

Before delving into the tapes themselves, it is important to provide context, especially in light of the fact that more than half of today’s New Yorkers were not yet born in the early 1980s, and many of those who were alive then, moved here well after, so they have no empirical point of comparison.

At the time, the city had been in decline for more than a decade, starting with labor strikes and riots in the 1960s, followed by middle class flight to the suburbs and a major fiscal crisis in the mid-1970s, epitomized by the infamous 1975 New York Daily News headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” after President Gerald Ford denied federal funds to bail out the ailing metropolis.

Three mayors struggled to stop the hemorrhaging: well-healed, Yale-educated Republican John Lindsay (who switched to the Democratic Party during his second term); Democrat Abe Beame, who grew up in a New York tenement and graduated from City College; and the ever-colorful Ed Koch, who took over in 1978 in the wake of the Son of Sam killings and the 1977 citywide power blackout.

Koch was mayor during my taxi driving summers. He came across as a somewhat buffoonish, but likeable champion, fighting to turn the city around against overwhelming odds, regularly appearing in public, asking “How’m I doin’?” But significant improvement would take at least another decade.

In the early 1980s, the city’s nearly 12,000 yellow cabs dominated the Manhattan streets, ferrying half a million passengers a day. They were supplemented by another 22,000 for-hire vehicles, including limousines and livery (mostly radio-dispatched) cabs serving passengers in the outer boroughs.

Today, the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) still licenses nearly 14,000 yellow cabs, along with about 23,000 limos and livery cabs. But several thousand taxis sit idle every day, more or less out of circulation. Yellow cab traffic has plummeted to 120,000 rides per day, overshadowed by Uber and Lyft, which count more than 80,000 vehicles and nearly 670,000 trips per day.

To become a New York City taxi driver in the early 1980s, I had to obtain a chauffer’s license from the Department of Motor Vehicles, then pass a TLC written test, which was open book, meaning you could use a map book of the city to answer questions about its geography and how to get from one location to another. One document in my taxi file is titled “New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission Taxicab Driver Test Results,” stamped in blue ink: PASSED GEOGRAPHY TEST.

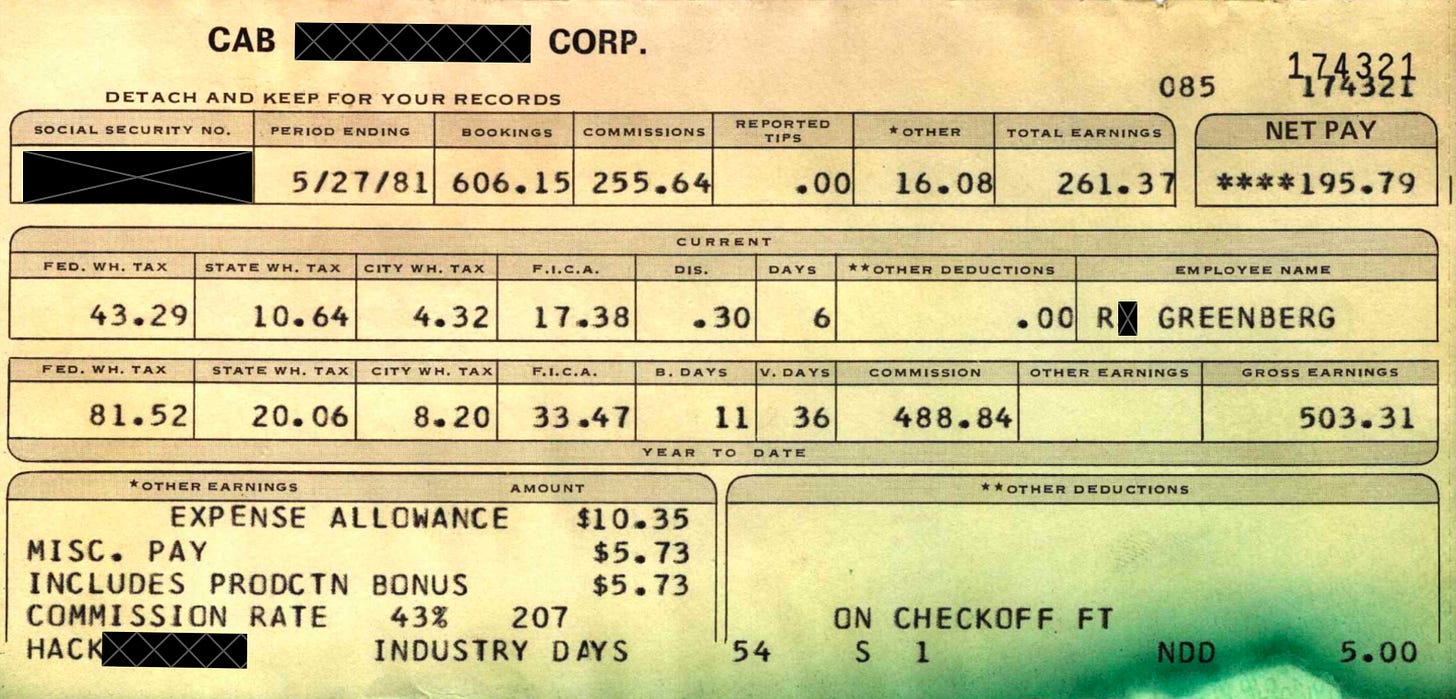

When I started driving, I received a percentage of each fare. In my “Taxi Stuff” envelope, I discovered a pay stub from May 1981, showing total weekly earnings of $261.37, which represented 43% of total bookings. Tips were separate and averaged around $20 to $25 a day.

By 1982, most of the industry had shifted to leasing, and I paid $45 to $55 a day to the company to rent the cab for 12 hours. After the daily lease fee, gas, and a union fee, I earned about $100 a day, or $500 to $600 a week, including tips. (In 2025, adjusting for inflation, that is the equivalent of about $1,600 to $1,900 a week.)

The Queens-based fleet for which I drove operated several dozen Checkers, whose design had barely changed since the 1950s. The Checker held five passengers, with a bench seat for three, ample leg and storage space, and two jump seats just behind the driver’s seat.

Starting with my morning commute to the garage at 4:15 AM, I noted the pervasiveness of crime. On the seven-minute walk from my apartment to the 96th Street subway station on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I usually passed several pimps, prostitutes and drug addicts, and sometimes witnessed violent altercations among them.

Data confirm that crime rates, across the board, were astonishingly higher. In 1981, the city counted 1,832 murders; in 2024, 382. The number of robberies exceeded 107,000 in 1981, but, 16,580 in 2024, an 84% drop. The transit system has witnessed a similar improvement: with more than 15,000 crimes reported in the subways alone in 1981, but, in 2024, 2,211- on subways and buses combined. (Following an increase in reported crime following the COVID pandemic, most rates have declined again over the past few years. The most notable exception is rape, with nearly 1,750 cases reported in 2024, up 19% over the previous year, though far fewer than the 3,862 rapes reported in 1981.)

One morning, while riding the subway to Queens to pick up my cab, I saw three young thugs harassing a young woman, clearly on her way home from an overnight shift. They surrounded her and taunted her with sexual comments.

As I was one of the only other people in the subway car, I felt in no position to confront them. Instead, I got out at the next station, went to the token booth – they were manned back then – and reported the ongoing incident to a clerk, who in turn called the police. I was left fretting about the passenger’s fate, hoping that the men did not assault her, and wondering if the police would manage to respond in time, or even at all.

After emerging from the Queens Plaza subway station, I would walk a few blocks to the taxi garage on Jackson Avenue.

Taxi garage, Queens, Summer 1982

Most mornings, I passed a group of prostitutes, often a dozen or more, many wearing shiny miniskirts or skintight pants, and bright tops, baring as much cleavage as possible, sometimes even pulling down their tops to show off their naked breasts. Their desperation was palpable. Local pimps were never far away.

One morning, I stumbled over a scorched seat cushion, a remnant from a burnt-out Volkswagen bus, which had been part of the neighborhood scenery for several weeks, one of the countless stolen, abandoned vehicles littering the city landscape.

Last year, the New York Post decried a “surge” in car theft, hitting 15,802 in 2023; in 1981, the number was 100,900, more than six times higher. (In 2024, the number dropped to 13,000.)

The massive amount of auto theft fed an equally massive illegal trade in auto parts. Thieves rarely faced significant punishment. As The New York Times reported at the time: “In 1980, the most recent year for complete city records, there were about 9,000 felony motor vehicle arrests in New York City, but the city sent only nine persons to prison for that crime, the police said.”

There seemed to be a higher level of tolerance for many of the city’s vices. Drug deals took place openly on street corners. And sex workers frequently operated without police interference.

Several times, local sex workers and/or their pimps hailed my cab at the start of my shift. One woman described working seven days a week, to earn as much money as possible, then leaving the city for an occasional break. “When I take time off,” she told me, “I need time off, like three weeks.”

Another was joined by her pimp, the pair heading from Long Island City to Brooklyn. As soon as she was firmly ensconced in the back, she pulled off her wig of long faux curls, which reeked of sweat and grime, exposing her nearly bald head. She and her companion snorted a few lines of cocaine and started having sex, seemingly unconcerned that I was witnessing it all. As annoying as that was, I grew even more annoyed when they got out at their destination and gave me zero tip.

A third trip involved a pimp and his brother, both clearly very high – not totally incoherent, but not always easy to understand.

As we headed away from the Queens Plaza area, one asked me about the women on the corner: “How do you think them girls look?”

Awkward response from me: “They look pretty nice. Young.”

I changed the subject: “You guys been out all night?”

Passenger: “Yeah.”

Me: “Must be pretty tired.”

Passenger: “Yeah. We used some cocaine.”

Me: “Huh?”

Passenger: “We used some cocaine.”

They wanted more coke, and I apparently was taking them to score it.

In the early 1980s, cocaine use was on the rise, with New York on its way to becoming the epicenter of the crack epidemic. Heroin already had ravaged the city, with an estimated 172,000 to 200,000 addicts, or about 1 in every 40 residents.

Figures for the number of addicts today are hard to come by, but the number of drug-related deaths is one of the few metrics that has changed for the worse – and drastically – with 3,046 overdose deaths reported in 2023 versus 511 drug-related deaths in 1981. (New York City statistics for 2024 are not yet available, but the CDC reported a nearly 17% decrease in overdose deaths nationwide between July 2023 and July 2024.)

On June 7, 1981, the annual Puerto Rican Day parade was underway, a spirited event known for its over-the-top floats, musical performances, and exuberant crowd. I was steering clear of the parade route when a young woman hailed my cab in the West Village. Diminutive in stature, she was sporting very dark sunglasses, her reddish-brown hair tied back with a blue headband pushing her hair upward. Clad in black shorts, a black top and red shoes, she had the air of many Village dwellers, a bit punkish and yet original. I also noted on tape that her pale face was jaundiced or “discolored yellow.”

“Seventy-second and York,” she said as she slid into the bench seat, an Upper East Side location on the other side of the parade route. I recall detouring via the FDR Drive that runs along the East River to avoid the inevitable parade traffic jams.

Her destination was a modern luxury high-rise, with a fountain out front and a driveway, a rarity in Manhattan. She asked me to wait, because then she wanted to go back downtown.

After about ten minutes, she returned, and I was taken aback when she announced her next destination: East 9th Street, between Avenues C and D. In 1981, that neighborhood, known as Alphabet City, was among the most dangerous in all of New York City. Many of the buildings were abandoned, burnt-out and occupied by drug addicts.

Carrying a large shoulder bag, she did not hesitate as she confidently strode over to one of the abandoned buildings and approached two men standing out front: a large Black man, who resembled a nightclub bouncer, wearing a baseball cap, and a thinner white man wearing a checked shirt and what I described on tape as a “fisherman’s hat.”

I was watching it all from inside my cab. It was about 80 degrees that day and humid, and normally, my windows would be open, but, under the circumstances, I rolled them up and made sure the doors were locked. Three teens walked by, one playing with a switchblade. They paid me no mind. Moments later, a woman who looked to be in her twenties passed in the other direction, two children in tow.

While waiting outside the building, my passenger chatted up a third man, who I noted also was wearing sunglasses. After a few minutes, the big man emerged and handed her a bag. As she headed over to the cab, I unlocked the doors, and she climbed in.

“Back to Seventy-second and York,” she declared, as she reached into the bag and pulled out what appeared to be a plexiglass tray. She set it down on her lap, along with what I estimated to be a gallon-sized plastic bag half-filled with white powder. From that mound of cocaine, she scooped out a smaller pile, which she then transferred to a smaller plastic bag.

After she apparently delivered the cocaine to her patron, we headed downtown yet again. Stuck in parade-related traffic, the young drug dealer opened up about her life, especially her affluent upbringing. She explained that she had grown up on the Upper East Side and attended private school. Like many wealthy families, hers hired a nanny.

“When I was little, I had a nurse, and she was the worst,” she said. “She was this French lady, and whenever she got into a taxi, everything was wrong.” When one driver refused to turn off his radio, she recounted, the nurse stormed out of the cab. “I was only about five years old, and I was so embarrassed whenever I went anywhere with her.”

Before I could find out what led her from that privileged life, the passenger, frustrated by the stalled traffic, informed me she would walk the rest of the way to her destination.

In addition to ferrying around people who trafficked in sex and drugs, I also drove for their customers. Early one morning in June 1982, a man in his twenties hailed me on Park Avenue South. Energetic and loquacious, he boasted that he had won hundreds of dollars at a dog track near his hometown of Philadelphia and traveled to Manhattan to enjoy his windfall.

His current destination was not so much a place, but an objective: he wanted to find a prostitute willing to go back to his hotel and spend the day with him.

He announced proudly that he was staying at the Seville Hotel on Madison Avenue and 29th Street, around the corner from where I picked him up. At the time, the Seville, a Beaux-Arts beauty built at the start of the 20thCentury, had seen better days, and its bargain daily rates were advertised regularly on local television stations.

Initially, I wondered why he bothered to hail a cab, because, on most days, that very neighborhood was teeming with sex workers, but, on this June morning, there were just a handful, and none interested in his proposition.

He asked me to take him to another neighborhood where he might find “success.”

“I got some good cocaine,” he said, adding that he intended to use it to lure a woman to go back to the Seville.

Awkwardly, I explained that different neighborhoods had different types of sex workers. Further west in Manhattan, there were trans women, usually loitering just north of the Meatpacking District. There were plenty of hookers in the Times Square area, I told him, and also on the Lower East Side, along Chrystie Street, where many also were drug addicts.

He opted for Chrystie Street.

En route, he asked if I would “take care of the business,” meaning solicit the women for him. I politely declined and told him that he needed to do it himself.

In June 1982, HIV/AIDS had not fully entered the public consciousness, and to the degree there was awareness of an emerging epidemic, news stories at the time focused on transmission among gay men.

Still, observing this sordid interaction raised serious concerns about public health, mental and physical. Many of the women on Chrystie Street had needle tracks on their arms. Some had visible sores on their faces.

None of that deterred my passenger, who did not want to leave the cab, preferring to call out to them through the open window. “Hey. How ya doin’?” he said to the first woman he approached, “Let me ask you. Come here. Come here.” He explained that he had cocaine and wanted her to go back to his hotel. “Here’s the deal,” he said. “I’m on 29th Street and Madison.”

Her immediate response: “I don’t want to go. I don’t want to go over there.”

After some back and forth, she proposed that he go upstairs to her place nearby.

Passenger: “Ain’t nobody upstairs with you? I’m cash money. I ain’t fucking bullshit. I’m trying to be straight up…. I’m just sayin’, ain’t nobody up there but you? I’m be spending money today. I want to make sure things stay cool and no n*****s jumping on me.”

Woman: “Nobody botherin’ you.”

Passenger: “Alright. It’s cool.”

Woman: “Have a nice day.”

As we pulled ahead, he commented, “That bitch look like a dirt bag.”

“She looked like a drug addict,” I replied.

He tried two more women, who also rejected his approach. He seemed ready to call it a day, but then, he noticed a woman exiting from a tenement building and heading north towards Delancey Street.

The passenger called out to her: “How you doing sweetheart? What ya doin’? What’s up mama? How ya doin’? Listen, I’m stayin’ at the Seville Hotel on Madison.”

Woman: “And this is at where?”

Passenger: “Madison and 29th Street. I’m giving you 20 dollars, plus five dollars for a cab.”

With that, she climbed inside and shut the door.

Clearly enticed by the cocaine, she did not want to wait to get back to the hotel to get high.

“Give me a hit of that stuff!” she said.

He eagerly served her a few lines, which she snorted immediately, telling him, “You seem like a cool guy.”

As they stepped out at the hotel, I contemplated their dire situation and likely bleak future.

Amid that kind of gloom, I managed to approach each morning with enthusiasm. I could not wait to get into my cab and cross the Queensboro Bridge. I knew that within an hour the sun would be rising, often casting a magical pink and orange glow across the city.

Upper East Side, Manhattan, early morning, Summer 1982

As it grew higher in the sky, the sun’s reflection gleamed in the glass skyscrapers, like the Citicorp Center on East 53rd Street and Lexington Avenue, and the Pan Am Building that towered over Grand Central Terminal. (Purchased in 1980-81 by Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, the building retained its Pan Am sign until 1993, more than a year after the legendary airline stopped flying.)

Many mornings, I found serenity cruising up and down Manhattan’s main avenues, windows open, cool air streaming in while I scoured the streets for fares. By mid-morning, though, as the temperature rose, the air would thicken. With no air conditioning, my cab turned into a sweatbox, even with windows open. At every stoplight, exhaust fumes wafted in, making breathing all the more difficult.

In many neighborhoods, piles of trash rotting in the summer heat made the air more fetid. While many visitors may consider today’s streets dirty and rat-infested, back in the early 1980s, they were measurably much dirtier.

For a half century, the city Department of Sanitation has kept a scorecard of street cleanliness, rating the percentage of streets that are “acceptably clean.” In 1981, only 57.5% made the grade.

In a July 1981 New York Times interview, Mayor Koch promised to step up sanitation efforts, but conceded that “many New Yorkers are slobs” and that even an expanded force of 1,250 street cleaners “cannot clean up after seven and half million New Yorkers.”

By the following year, 1982, street cleanliness improved to 63%. Successive administrations continued the push, and, by 2023, the score reached 93.5%.

Beyond questions of sanitation, in the early 1980s, the roadways themselves were a shambles, the most visible sign of the city’s atrophying infrastructure.

In July 1983, the Times described Mayor Koch as presiding over “an empire of potholes, more than 700,000 of them a year, and over a crumbling road system that is the legacy of long neglect.”

Unable to fill those holes in a timely manner, the city Department of Transportation (DOT) allowed some to grow so large they could cause an axle to break. Periodically, I would pass an immobilized taxi - which, for some reason, it seemed to me, tended to be smaller Dodge sedans - axle broken, one wheel stuck in a pothole.

(By comparison, the city’s 311 system received 41,907 complaints of potholes in 2024; at the end of the year, the DOT reported filling a total of 500,000 potholes from 2022 through 2024.)

The broken streets constantly battered my Checker. On the tapes, you can hear the persistent rattling of the chassis.

You also can hear the moment my car went into a dangerous skid while on the Queensboro Bridge. Back then, the roadway was metal and became particularly slippery in the rain. I was in the midst of describing what it was like to cross the bridge in thick, early morning fog. “I’m halfway across the bridge and I’m just beginning [skidding sound]. “This car just hit an oil slick or something.”

I struggled to stop the car from crashing into a limousine, then resumed my narrative. “I was going 35 miles an hour, and my car went into a spin like I’ve never felt before. I don’t know what it was, but it sent me clear across both sides of the bridge, back and then forth, pretty fucking scary, and I turned into the spin, and I cut myself from going one way and sent myself back the other and luckily, I came out okay.”

Beyond the bridges and beneath the roadways, the then-80-year-old subway system also was in critical disrepair. After 12 hours sweating in traffic, I would jam into the packed, noisy, sweltering subway for a miserable ride home, often made more miserable by persistent delays at Times Square, where I had to change trains.

Subway cars broke down on average every 12,000 miles, so frequently, that, in early 1981, a quarter of all subway cars were out of service at any time, according to a January 1982 New York Times Magazine article. Today’s subway, by contrast, with its fleets of air-conditioned cars suffers only a fraction as many breakdowns, with cars traveling more than 140,000 miles between failures.

One problem that is much worse now than back then is the cost of housing. In the summer of 1981, I sublet a one-bedroom apartment from a college professor for $350 a month (about $1,200 now adjusted for inflation), less than one week of my pay as a taxi driver. Today, a similar apartment costs $5,000 a month. Real estate data show the median monthly rent in 1981 was $265 ($895 adjusted for inflation), but in October 2024, it hit $3,686, according to StreetEasy.

Even with much lower rents back then, many people fell behind on payments and faced eviction. The city issued 26,775 eviction orders in 1980, but fewer than half as many, around 12,000, in 2023.

A passenger in his early seventies, recently retired and fresh off a bus from a family visit in North Carolina, recounted his ongoing dispute with his Brooklyn landlord. “I’ve been overcharged for the last 15 years,” he said. I’ve been living there 16 years and I’ve been overcharged 15.”

He discovered the problem, he said, when he helped a neighbor whom the landlord threatened with eviction after increasing the rent overnight from $129 a month to $200.

The passenger took his neighbor to see a Legal Aid lawyer, who reviewed their rent-controlled status under city regulations and determined that both men were being overcharged.

After months of legal wrangling, the lawyer succeeded in getting the neighbor’s rent reduced. “You know what he has to pay a month now?” he asked rhetorically. “Seventy dollars and 44 cents.”

His own case was still tied up in court, he said, and the landlord was not happy. So much so that he believed the landlord was behind a recent attempt to rob him in the building lobby. He said that when he entered the vestibule, normally accessible only with a key, around 8 PM, a young man inside confronted him, demanding he hand over his money.

“I says: ‘Well, I got 40 cents in my wallet. You want that? You got it.’ The guy looks at me, laughs, and walks out of the building.”

He theorized, aware he had no proof, that the frustrated landlord had given the robber a key to the building in order “to shake me up or make me afraid.”

Crime in the area ran rampant, he lamented, confiding that, weeks earlier, a woman had carjacked and robbed him at gunpoint, approaching his open car window.

“She took the car, too, and my money also,” he said. “I think I had about some 80 dollars and change. She made me give the change, too. I didn’t have money even to make a phone call home, to tell my wife to get out the money ready for a cab fare.”

Fortunately, he said, he recovered the car, but not his wallet. “You gotta be tough to survive in this neighborhood”.

Not everyone shared his grit and ability to navigate the system, especially the tens of thousands living on the streets, without shelter.

One morning, social workers from the Salvation Army hailed my cab on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, not far from the Bowery, an area with a high concentration of homeless.

They helped lift a frail and unbathed man, inside, directing me to drive him to a nearby shelter. Nauseated by his foul body odor, I opened the car window and sought relief from the stagnant summer air. He appeared to be perhaps in his forties, had rotting teeth, his clothes turned to rags, and his hair a long, matted nest.

He told me his name was Joseph Shapiro and he had been living on the streets for over three years, spiraling downward after his parents died. “I lost my job, and I couldn’t find work. I had no one to help.”

He described his gradual descent into isolation, until he no longer bothered to communicate with others and took to carrying on dialogues with himself instead.

He did not blame others for his alienation, and now had attained a level of clarity and self-awareness that I found surprising. “Do you think they can help me?” he asked. “Do you think I’ll get better?”

Over the past four decades, the number of people living on the city streets has dropped sharply, from 36,000 in 1981 to 4,140 in 2024. (Housing advocates dispute the methodology used in the annual census. The Coalition for the Homeless says there is “no reliable estimate,” stating only that the number of unsheltered is in the “thousands.”)

Certainly, the expansion of the city’s shelter system has helped, increasing from 3,200 beds in 1981; in December 2024, shelters housed nearly 125,000 people per night.

But, decades of rent increases outstripping pay increases have exacerbated the housing shortage, and the influx of migrants over the past few years has compounded the problem.

In spite of the surge in shelter beds and the development of tens of thousands of new affordable housing units, the city cannot keep up. The rental vacancy rate already tight at 2.13% in 1981 is far tighter now at 1.4%.

As dire as it may seem, the current situation pales in comparison with Mayor Koch’s first term (1978-1981), when more than 81,000 housing units, mainly in poorer neighborhoods, disappeared, many of them destroyed by arson fires. In 1980, the city suffered nearly 9,000 such fires. (In 2023, there were just over 1,000.)

South Bronx, Summer 1982

Entire blocks in the South Bronx looked like war zones, including one particularly hard-hit area nicknamed Fort Apache.

“It makes you cry. It’s really a sad, sad sight,” said a passenger who grew up near Fort Apache and still lived in the South Bronx. “To see the burnt-out buildings burnt-out like that is a disgrace.”

He was heading home after visiting his ailing father at a nursing home in Queens. When they moved to the Bronx in the 1960s, he said, the neighborhoods were clean and safe.

Now, he said, “drugs and numbers” ruled, referring to the widespread “bookie joints,” often hidden behind a front business, like a toy store or dry cleaner.

As we passed along one of the main streets, dotted with the carcasses of stolen cars, he told me, “I try not to let my wife drive around here. It’s too dangerous for her to be around here. They snatch your purse and run off.” Police did not usually pursue the criminals, he added.

As I dropped him off, he advised me not to stop at the red lights on the way out of the neighborhood. “Be careful,” he warned, “They won’t give you a chance.”

But what disconcerted me most about our conversation was the animosity he expressed in analyzing the situation. A Black man himself, he blamed “low-class” Blacks and Hispanics for the plight of the neighborhood, along with “Jewish landlords” who, he asserted, paid “these animals to burn down their buildings” so they could collect insurance money and abandon the properties.

The city has long suffered from an undercurrent of racism and hatred, exacerbated by rivalries among various immigrant, ethnic, and racial groups.

Some passengers apparently felt the anonymity inside the cab made it safe to use hate-filled rhetoric.

A passenger who identified himself as a New York judge repeatedly used the N-word in talking about crime in the city and told me he was eager for the death penalty to be restored. He cited a “typical” case, in which a man accused of shooting his wife and daughter admitted committing the crime but defended himself by claiming that he was drunk at the time and just lost control.

When I said I thought that was horrible, the judge replied: “What do you expect? He was just a lousy, fuckin’ n*****!”

Talking about rising crime rates, an elderly Jewish man used a Yiddish epithet to refer to Blacks and called Puerto Ricans “spics.”

Hateful words can lead to hateful acts. Early one morning, I picked up a young gay man in the West Village, who had deep scars across the right side of his head and face, clearly from a recent trauma.

“A few months ago,” he recounted, “in the evening, while it was still light, I was walking down Christopher Street near Sixth Avenue, when a group of nine kids came up to me, called me a faggot, and then kicked the shit out of me. They were nine and I was one, and nobody on the street stopped to help – and no cops came.”

They knocked him to the ground, he said, then kicked him repeatedly in the groin, chest and face. When he looked up to see if they were leaving, one of the kids came running back and kicked him in the eye, “as if my head was a football,” he added. “I thought I’d lost my eye.”

As the assailants fled toward Washington Square, he said, passersby ignored his requests for help, until an elderly man hailed a police officer who called in others. The officers chased down the group, scuffled with, and then arrested them, according to the victim.

At the trial, he said, his attackers showed up wearing jackets and ties. Their parents were “teary-eyed” claiming their children were good and would not harm anyone. He said social workers also testified on behalf of the accused. “I didn’t have a chance,” he told me. The group was given probation. “So, then I was really glad the cops had at least gotten in a punch or two.”

At the time, New York did not have a hate crime law covering sexual orientation, nor did the city collect data on such crimes. Today, a case like that likely would draw press attention and result in much stiffer sentences, thanks largely to hate crime legislation enacted over the past twenty-five years.

Gay sex had become legal in New York only in 1980, following a landmark case that overturned the state’s anti-sodomy law. In the early 1980s, predominantly gay night clubs, with names like The Anvil and Mineshaft, held sway in downtown Manhattan.

Many mornings, in the wee hours, passengers emerging from a full night of partying would recount their adventures. Some were still on cocaine highs. Others more subdued, like a young man whose visage, long neck and hair shooting upward reminded me of the lead character in David Lynch’s cult classic film Eraserhead. He had been out all night and expressed frustration to be going home alone. Then, out of the blue, he propositioned me: “Well, I know it’s kinda early in the morning and everything, but how would you like your cock sucked?” After an awkward pause, I responded with a slight laugh, “No thank you.”

Another early morning passenger confessed that he had a fetish for shaving his sexual partners. Coincidentally, or not so coincidentally, he worked at a major hospital shaving patients in preparation for surgery.

Yet another seemed fixated on serial killers. After a night of revelry, the 35-year-old was heading uptown, offering a lift to a woman he had just met at a downtown club.

At the outset of the ride, he brought up the dangers of meeting people randomly in New York, invoking the case of David Berkowitz, aka Son of Sam, which had terrified the city only a few years earlier. He suggested a new serial strangler might be targeting women in Manhattan.

I could not figure out if he was trying to foment fear or was just morbid in general.

The woman uncomfortably brushed off his comments and changed the subject, clearly eager to extricate herself from the situation.

After we dropped her off, he brought up the stranglings again, as he described the hazard of the anything-goes atmosphere in some clubs, where sex was free-flowing and anonymous. “They don’t know you from Adam,” he explained. “Like I was telling this girl here with the – like Berkowitz, there’s a strangler going around, could be you go with a stranger, and they strangle you.”

He worried that one of his recent girlfriends might be a victim. “Now she’s missing two weeks.” I was taken aback. “Missing?” I asked as I pressed for details. “Are other people missing her?”

Passenger: “Yeah, they don’t know where she is.”

Me: “Like her relatives?”

Passenger: “Relatives, she don’t have any relatives. That’s the whole thing, you know.”

Amid his jumbled answers, he confided she was a heroin addict.

Passenger: “When she got with this drug business, I got scared. She was shooting up and all that shit. I didn’t get involved with that, so I didn’t call her for like two months.”

Me: “Was she really shooting up?”

Passenger: “I never saw that in my life. It looked like that movie with Al Pacino, Panic in Needle Park. So, I got scared. So, I didn’t call for a month-. I told her the reason why. Someone told me she’s like in rehabilitation now. She’s got a methadone. They put her in a clinic or something.”

Me: “So there are a bunch of different stories circulating about her?”

Passenger: “Yeah. So, nobody knows.”

Random crime, especially involving guns, contributed to an air of menace that hung over the city, like the case of a sniper who shot six passersby from the upper floors of a Brooklyn apartment building.

One morning in Times Square, while stopped at a traffic light, a man in the car next to me leaned out of the window, gesturing toward a prostitute on the side of the road, “Hey, she’s nice, huh?” he yelled at me. He then waved a large handgun, asking sinisterly if he and his friends should take her and “blow her brains out.” Their car lingered behind as I pulled forward. Looking in my rearview mirror, I tried to take down the license plate, but could not get it in time.

Nearly 60 percent of the 1,832 murders in 1981 involved handguns. Twenty-one of the victims were New York City cab drivers; 62 others were wounded that year. (Many drove livery cabs, not yellow cabs, in dangerous neighborhoods.) Today, shootings of drivers are relatively rare.

I had one uncomfortably close encounter with a gun, pulled by another taxi driver in an apparent road rage incident. With a couple of German tourist passengers in back, I was heading down Broadway, near Lincoln Center, when the other driver suddenly accelerated, swerved in front of me and stopped short, forcing me, in turn, to stop. He jumped out of his cab and approached my window, clearly irate, pointing a pistol at me, screaming that I had cut him off. I was not aware of having done so, but in the moment it did not matter.

One passenger shouted in German: “Aber das ist doch eine Pistole! Er hat eine Pistole!” Fortunately, the armed driver had left enough room for me to squeeze my cab past his, so I pulled around and floored it.

The driver hopped back into his car and gave chase. A few blocks later, he cut me off and ran over to my cab again, this time without the weapon. Instead, he furiously pounded the Checker hood with his fists and kicked the fenders and doors, repeatedly swearing at me. Then, he walked back to his cab and drove off.

Several drivers I knew carried guns for self-protection, including one from our fleet who took me aside at the end of a shift to show me his .38, which he stashed under the front seat. He was an affable man, in his forties, who sported an Afro and long sideburns, a style reminiscent of the actor Clarence Williams III in the late 1960s-early 1970s hit television show, Mod Squad. He enjoyed sharing advice with younger drivers like me and recommended that I consider carrying a weapon, too.

Fortunately, in my three summers as a taxi driver, I was not a victim of serious crime. I did get ripped off about five times by passengers who left the cab without paying. Most of the perpetrators were elderly, including a couple in their seventies leaving a doctor’s office on Central Park West. As we were heading to their supposed destination, they asked to stop at a bank to cash a check to pay for the ride. They never came back.

The anecdotes above may foster a misleading impression that I dealt only with miscreants and desperate people.

But I also witnessed many heartwarming scenes, like a Queens couple taking their young son to catch a bus to sleepaway camp, his first extended time away from home. As the parents shifted nervously, the boy smiled with excitement. They talked about what a great time he was going to have. Then, in a tender moment, the father, holding back tears, said: “You’re gonna miss me.”

Lighter moments, like two Queens women in their fifties en route to a limerick contest in Manhattan, one sharing this verse: “New York’s international scene is superb. Marinated and basted in savory herbs. You don’t need reservations. You can’t beat the locations. It’s the pushcarts outside by the curb.”

Poignant interactions, like the wheelchair-bound young man making his way home to a housing project, alone, resolute in his determination to lead an independent life.

And inspirational stories: A nurse from Jamaica who realized her childhood dream of immigrating to New York City, a dream spawned by her father who had visited in the 1940s.

“He used to sit down at night, you know, because we didn’t have radio, we didn’t have television, and he used to tell us all these stories,” she recalled. He mesmerized her and her siblings with descriptions of Park Avenue luxury and Fifth Avenue stores, trains and buses, and the excitement of Broadway. When they later saw Pan Am planes flying overhead, she recounted, “we used to jump up and say: ‘Take us to America!’”

Now that she had fulfilled her dream, I asked how her life had turned out. “Well, my life’s been here – I can’t complain, really, you know, I really can’t complain,” she answered haltingly. “I work, you know, and I can’t complain.” After a slight pause, she divulged, “I was mugged a couple of times,” adding with a nervous laugh, “but I’m doing fine, you know.”

In the moment, it came across as a reality check. Grateful for the opportunity New York had afforded her, she also understood the peril that lurked. Her attitude reaffirmed that living with a sense of history can act as a tempering force. If you identify and understand positive change that has taken place, you might have a less pessimistic view when bad things happen.

That certainly was the approach a passenger named Mario, a 65-year-old, who grew up in the thick of the Depression, his first job as a longshoreman. “When I was 15,” he reminisced, “1932 – I went to work on the docks.” He said he had ten siblings, and his father brought home perhaps $13 a week (the equivalent of about $285 in 2024).

Before long, Mario was earning $18.75 a week, supporting himself and helping his family. “I had a car,” he said with great pride. “At that time, for a thousand, you’d buy a new Dodge or DeSoto, whatever, you know, like a thousand dollars.”

After 20 years on the waterfront, in the early 1950s, Mario changed it up and took a job in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan. In his 30 years there, he earned a solid living, paying for a house, raising two sons with his wife. One son, he told me, was now a vice president with a major financial company, the other a magazine editor. “I put ‘em through school, college, everything, and everybody’s happy.”

In retirement, Mario was still working, running a shoeshine business and selling steak to Wall Street executives. He said he prized his fortune in life, his rise from poverty, his decades of hard work and marriage culminating in two prosperous children. “My motto is this: you help people out, people will help you out. ‘Cause you need people. If I didn’t have friends out here, where would I be?”

The day before I met Mario in early August 1982, another successful child of Italian immigrants rode with me, my most famous passenger: Joe DiMaggio, the Yankee slugger famous on the field for his record 56-game hitting streak (which still stands) and off the field for his marriage to Marilyn Monroe.

Outside Grand Central Station, a nondescript businessman in a gray suit hailed my cab and asked me to take him to the Sheraton Centre hotel on Seventh Avenue and 52nd Street. Along the way, he told me we would be picking up another passenger, asking nonchalantly if I would mind “waiting for Mr. Joe DiMaggio.”

When he went inside to collect “Mr. DiMaggio,” I could not contain my excitement at the prospect of meeting the baseball legend. “What do you know,” I said into my cassette recorder, “I’m about to get Joe DiMaggio in my cab!”

I fidgeted as I considered all the questions I wanted to ask him about his years in pinstripes and about the recent downturn in the Yankees’ performance. (The team finished fifth in the American League East in 1982.) Not to mention, what did he really think about Marilyn Monroe’s death?

The 67-year-old had played his last season with the Yankees in 1951, more than 30 years earlier. Starting in the 1970s, DiMaggio worked as a front man, regularly appearing in ads for Mr. Coffee and for The Bowery Savings Bank.

As he left the hotel, a few heads turned to watch the stately DiMaggio enter my cab with his companion.

It turned out they were preparing to shoot another Bowery commercial, and the man who hailed the cab was an advertising manager for the bank. We were heading straight down Seventh Avenue to 17th Street, to Barneys, the clothier renowned for its enormous selection of men’s suits.

Now was my moment, I thought. Confident that I had learned to talk to anybody, I tried to conjure up a natural conversation-starter, but quickly found myself tongue-tied.

Much to my chagrin, the baseball hero sat mostly silent, and when he did speak, his voice was so soft, I could barely discern a word. On tape, it sounds like muffled mumbling.

As we arrived at Barneys, the ad manager handed me $12, $6.40 for the fare and a 53% tip. The two men offered a polite good-bye and headed into the store.

That same day in August, as I drove along Central Park South, I passed a carriage horse that had collapsed. It lay on the ground on its side, medical personnel trying to revive it. The police and press were there. So was the ASPCA. The next morning, I learned that the horse did not survive, the fourth to die in less than three weeks.

At the end of my shift that afternoon, one of my last as a taxi driver, I remarked it was an apt metaphor for the ailing city. Was a total collapse inevitable or could New York City be saved?

“The roads are a shambles. The subways are a shambles. The streets are a shambles,” I memorialized on tape, lamenting the crime, decay, and despair. “People don’t care enough. They throw the garbage out of their car windows, out of their house windows, as they’re walking down the streets. People just don’t seem to act until they face absolute crisis.”

Back then, I doubted the city could summon the will to act, figuring apathy and entropy would prevail. I did not foresee the notable improvements that would ensue over the next four decades.

Today, tabloid media and disingenuous politicians are tossing another type of trash –hyperbole – into the public square, their propagation of a false narrative seemingly designed more to stoke fear and anger than to improve city life.

To make real progress in addressing New York’s shortcomings, our thought leaders and policymakers will have to sift out that trash and focus on hard facts about crime, drugs, mental illness, housing, and transportation.

They could start by asking a cabbie.

It’s a wonderful ride-along, filled with great anecdotes. You should have told DiMaggio to speak up!!!

Thanks Rich for bringing back so many memories of that time in NYC. One of my earliest memories was when my dad took me to the circus at MSG. Mayor Lindsey was introduced before the event and was literally booed out of the arena!!